Remembering Michael Jackson: The Story Behind His Magnum Opus

Before Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth, before Avatar and Wall-E, before "going green" became a catchphrase, came Michael Jackson's "Earth Song," one of the most unusual, audacious protest songs in popular music history. A massive hit globally (reaching #1 in over fifteen countries), it wasn't even released as a single in the United States.

Yet nearly sixteen years later, its admirers continue to grow. The song's desperate plea on behalf of the planet and its inhabitants (particularly the most vulnerable) remains as relevant and important as ever.

"Earth Song" mattered deeply to Jackson, who rightfully considered it one of his greatest artistic achievements. He planned for it to be the climax of his ill-fated This Is It concert series in London. It was the last song he rehearsed before he died.

The following excerpt is from a 50-page piece entitled "Earth Song: Inside Michael Jackson's Magnum Opus," which details the song's evolution from its inception in Vienna to Jackson's final live performance in Munich:

"Michael Jackson was alone in his hotel room, pacing.

He was in the midst of the second leg of his Bad World Tour, an exhausting, 123-concert spectacular that stretched over nearly two years. The tour would become the largest-grossing and most-attended concert series in history.

Just days earlier, Jackson had performed in Rome at Flaminio Stadium to an ecstatic sold-out crowd of over 30,000. In his downtime, he visited the Sistine Chapel and St. Peter's Cathedral at the Vatican with Quincy Jones and legendary composer, Leonard Bernstein. Later, they drove to Florence where Jackson stood beneath Michelangelo's masterful sculpture, David, gazing up in awe.

Now he was in Vienna, Austria, music capital of the Western world. It was here where Mozart's brilliant Symphony No. 25 and haunting Requiem were composed; where Beethoven studied under Haydn and played his first symphony. And it was here, at the Vienna Marriott, on June 1, 1988, that Michael Jackson's magnum opus, "Earth Song," was born.

The six-and-a-half-minute piece that materialized over the next seven years was unlike anything heard before in popular music. Social anthems and protest songs had long been part of the heritage of rock. But not like this. "Earth Song" was something more epic, dramatic, and primal. Its roots were deeper; its vision more panoramic. It was a lamentation torn from the pages of Job and Jeremiah, an apocalyptic prophecy that recalled the works of Blake, Yeats, and Eliot.

It conveyed musically what Picasso's masterful aesthetic protest, Guernica, conveyed in art. Inside its swirling scenes of destruction and suffering were voices -- crying, pleading, shouting to be heard ("What about us?").

"Earth Song" would become the most successful environmental anthem ever recorded, topping the charts in over fifteen countries and selling over five million copies. Yet critics never quite knew what to make of it. Its unusual fusion of opera, rock, gospel, and blues sounded like nothing on the radio. It defied almost every expectation of a traditional anthem. In place of nationalism, it envisioned a world without division or hierarchy. In place of religious dogma or humanism, it yearned for a broader vision of ecological balance and harmony. In place of simplistic propaganda for a cause, it was a genuine artistic expression. In place of a jingly chorus that could be plastered on a T-shirt or billboard, it offered a wordless, universal cry.

Jackson remembered the exact moment the melody came.

It was his second night in Vienna. Outside his hotel, beyond Ring Strasse Boulevard and the sprawling Stadtpark, he could see the majestically lit museums, cathedrals, and opera houses. It was a world of culture and privilege far removed from his boyhood home in Gary, Indiana. Jackson was staying in spacious conjoining suites lined with large windows and a breathtaking view. Yet for all the surrounding opulence, mentally and emotionally he was somewhere else.

It wasn't mere loneliness (though he definitely felt that). It was something deeper -- an overwhelming despair about the condition of the world.

Perhaps the most common trait associated with celebrity is narcissism. In 1988, Jackson certainly would have had reason to be self-absorbed. He was the most famous person on the planet. Everywhere he traveled, he created mass hysteria. The day after his sold-out concert at Prater Stadium in Vienna, an AP article ran, "130 Fans Faint at Jackson Concert." If the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, as John Lennon once claimed, Jackson had the entire Holy Trinity beat.

While Jackson enjoyed the attention in certain ways, he also felt a profound responsibility to use his celebrity for more than fame and fortune (in 2000, The Guinness Book of World Records cited him as the most philanthropic pop star in history). "When you have seen the things I have seen and traveled all over the world, you would not be honest to yourself and the world to [look away]," Jackson explained.

At nearly every stop on his Bad World Tour, he would visit orphanages and hospitals. Just days earlier, while in Rome, he stopped by the Bambin Gesu Children's Hospital, handing out gifts, taking pictures, and signing autographs. Before leaving, he pledged a donation of over $100,000 dollars.

While performing or helping children, he felt strong and happy, but when he returned to his hotel room, a combination of anxiety, sadness, and desperation sometimes seized him.

Jackson had always been sensitive to suffering and injustice. But in recent years, his feeling of moral responsibility grew. The stereotype of his naiveté ignored his natural curiosity and sponge-like mind. While he wasn't a policy wonk (Jackson unquestionably preferred the realm of art to politics), he also wasn't oblivious to the world around him. He read widely, watched films, talked to experts, and studied issues passionately. He was deeply invested in trying to understand and change the world.

In 1988, he certainly had reason for concern. The news read like chapters from ancient scripture: there were heat waves and droughts, massive wildfires and earthquakes, genocide and famine. Violence escalated in the Holy Land as forests were ravaged in the Amazon and garbage, oil and sewage swept up on shores. In place of Time's Person of the Year, 1988's cover story was dedicated to the "endangered earth." It suddenly occurred to many that we were literally destroying our own home.

Most people read or watch the news casually, passively. They become numb to the horrifying images and stories projected on the screen. Yet such stories frequently moved Jackson to tears. He internalized them and felt physical pain. When people told him to simply enjoy his own good fortune, he got angry. He believed completely in John Donne's philosophy that "no man is an island." For Jackson, the idea extended to all life. The whole planet was connected and intrinsically valuable.

"[For the average person]," he explained, "he sees problems 'out there' to be solved... But I don't feel that way -- those problems aren't 'out there,' really. I feel them inside me. A child crying in Ethiopia, a seagull struggling pathetically in an oil spill... a teenage soldier trembling with terror when he hears the planes fly over: Aren't these happening in me when I see and hear about them?"

Once, during a dance rehearsal, he had to stop because an image of a dolphin trapped in a net made him so emotionally distraught. "From the way its body was tangled in the lines," he explained, "you could read so much agony. Its eyes were vacant, yet there was still that smile, the ones dolphins never lose... So there I was, in the middle of rehearsal, and I thought, 'They're killing a dance.'"

When Jackson performed, he could feel these turbulent emotions surging through him. With his dancing and singing, he tried to transfuse the suffering, give it expression, meaning, and strength. It was liberating. For a brief moment, he could take his audience to an alternative world of harmony and ecstasy. But inevitably, he was thrown back into the "real world" of fear and alienation.

So much of this pain and despair circulated inside Jackson as he stood in his hotel room, brooding.

Then suddenly it "dropped in [his] lap": Earth's song. A song from her perspective, her voice. A lamentation and a plea.

The chorus came to him first -- a wordless cry. He grabbed his tape player and pressed record. Aaaaaaaaah Oooooooooh.

The chords were simple, but powerful: A-flat minor to C-sharp triad; A-flat minor seventh to C-sharp triad; then modulating up, B-flat minor to E-flat triad. That's it! Jackson thought. He then worked out the introduction and some of the verses. He imagined its scope in his head. This, he determined, would be the greatest song he'd ever composed..."

Yet nearly sixteen years later, its admirers continue to grow. The song's desperate plea on behalf of the planet and its inhabitants (particularly the most vulnerable) remains as relevant and important as ever.

"Earth Song" mattered deeply to Jackson, who rightfully considered it one of his greatest artistic achievements. He planned for it to be the climax of his ill-fated This Is It concert series in London. It was the last song he rehearsed before he died.

The following excerpt is from a 50-page piece entitled "Earth Song: Inside Michael Jackson's Magnum Opus," which details the song's evolution from its inception in Vienna to Jackson's final live performance in Munich:

"Michael Jackson was alone in his hotel room, pacing.

He was in the midst of the second leg of his Bad World Tour, an exhausting, 123-concert spectacular that stretched over nearly two years. The tour would become the largest-grossing and most-attended concert series in history.

Just days earlier, Jackson had performed in Rome at Flaminio Stadium to an ecstatic sold-out crowd of over 30,000. In his downtime, he visited the Sistine Chapel and St. Peter's Cathedral at the Vatican with Quincy Jones and legendary composer, Leonard Bernstein. Later, they drove to Florence where Jackson stood beneath Michelangelo's masterful sculpture, David, gazing up in awe.

Now he was in Vienna, Austria, music capital of the Western world. It was here where Mozart's brilliant Symphony No. 25 and haunting Requiem were composed; where Beethoven studied under Haydn and played his first symphony. And it was here, at the Vienna Marriott, on June 1, 1988, that Michael Jackson's magnum opus, "Earth Song," was born.

The six-and-a-half-minute piece that materialized over the next seven years was unlike anything heard before in popular music. Social anthems and protest songs had long been part of the heritage of rock. But not like this. "Earth Song" was something more epic, dramatic, and primal. Its roots were deeper; its vision more panoramic. It was a lamentation torn from the pages of Job and Jeremiah, an apocalyptic prophecy that recalled the works of Blake, Yeats, and Eliot.

It conveyed musically what Picasso's masterful aesthetic protest, Guernica, conveyed in art. Inside its swirling scenes of destruction and suffering were voices -- crying, pleading, shouting to be heard ("What about us?").

"Earth Song" would become the most successful environmental anthem ever recorded, topping the charts in over fifteen countries and selling over five million copies. Yet critics never quite knew what to make of it. Its unusual fusion of opera, rock, gospel, and blues sounded like nothing on the radio. It defied almost every expectation of a traditional anthem. In place of nationalism, it envisioned a world without division or hierarchy. In place of religious dogma or humanism, it yearned for a broader vision of ecological balance and harmony. In place of simplistic propaganda for a cause, it was a genuine artistic expression. In place of a jingly chorus that could be plastered on a T-shirt or billboard, it offered a wordless, universal cry.

Jackson remembered the exact moment the melody came.

It was his second night in Vienna. Outside his hotel, beyond Ring Strasse Boulevard and the sprawling Stadtpark, he could see the majestically lit museums, cathedrals, and opera houses. It was a world of culture and privilege far removed from his boyhood home in Gary, Indiana. Jackson was staying in spacious conjoining suites lined with large windows and a breathtaking view. Yet for all the surrounding opulence, mentally and emotionally he was somewhere else.

It wasn't mere loneliness (though he definitely felt that). It was something deeper -- an overwhelming despair about the condition of the world.

Perhaps the most common trait associated with celebrity is narcissism. In 1988, Jackson certainly would have had reason to be self-absorbed. He was the most famous person on the planet. Everywhere he traveled, he created mass hysteria. The day after his sold-out concert at Prater Stadium in Vienna, an AP article ran, "130 Fans Faint at Jackson Concert." If the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, as John Lennon once claimed, Jackson had the entire Holy Trinity beat.

While Jackson enjoyed the attention in certain ways, he also felt a profound responsibility to use his celebrity for more than fame and fortune (in 2000, The Guinness Book of World Records cited him as the most philanthropic pop star in history). "When you have seen the things I have seen and traveled all over the world, you would not be honest to yourself and the world to [look away]," Jackson explained.

At nearly every stop on his Bad World Tour, he would visit orphanages and hospitals. Just days earlier, while in Rome, he stopped by the Bambin Gesu Children's Hospital, handing out gifts, taking pictures, and signing autographs. Before leaving, he pledged a donation of over $100,000 dollars.

While performing or helping children, he felt strong and happy, but when he returned to his hotel room, a combination of anxiety, sadness, and desperation sometimes seized him.

Jackson had always been sensitive to suffering and injustice. But in recent years, his feeling of moral responsibility grew. The stereotype of his naiveté ignored his natural curiosity and sponge-like mind. While he wasn't a policy wonk (Jackson unquestionably preferred the realm of art to politics), he also wasn't oblivious to the world around him. He read widely, watched films, talked to experts, and studied issues passionately. He was deeply invested in trying to understand and change the world.

In 1988, he certainly had reason for concern. The news read like chapters from ancient scripture: there were heat waves and droughts, massive wildfires and earthquakes, genocide and famine. Violence escalated in the Holy Land as forests were ravaged in the Amazon and garbage, oil and sewage swept up on shores. In place of Time's Person of the Year, 1988's cover story was dedicated to the "endangered earth." It suddenly occurred to many that we were literally destroying our own home.

Most people read or watch the news casually, passively. They become numb to the horrifying images and stories projected on the screen. Yet such stories frequently moved Jackson to tears. He internalized them and felt physical pain. When people told him to simply enjoy his own good fortune, he got angry. He believed completely in John Donne's philosophy that "no man is an island." For Jackson, the idea extended to all life. The whole planet was connected and intrinsically valuable.

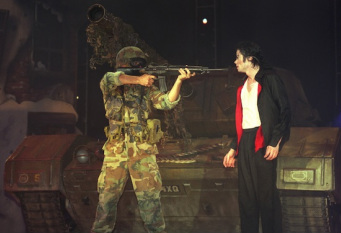

"[For the average person]," he explained, "he sees problems 'out there' to be solved... But I don't feel that way -- those problems aren't 'out there,' really. I feel them inside me. A child crying in Ethiopia, a seagull struggling pathetically in an oil spill... a teenage soldier trembling with terror when he hears the planes fly over: Aren't these happening in me when I see and hear about them?"

Once, during a dance rehearsal, he had to stop because an image of a dolphin trapped in a net made him so emotionally distraught. "From the way its body was tangled in the lines," he explained, "you could read so much agony. Its eyes were vacant, yet there was still that smile, the ones dolphins never lose... So there I was, in the middle of rehearsal, and I thought, 'They're killing a dance.'"

When Jackson performed, he could feel these turbulent emotions surging through him. With his dancing and singing, he tried to transfuse the suffering, give it expression, meaning, and strength. It was liberating. For a brief moment, he could take his audience to an alternative world of harmony and ecstasy. But inevitably, he was thrown back into the "real world" of fear and alienation.

So much of this pain and despair circulated inside Jackson as he stood in his hotel room, brooding.

Then suddenly it "dropped in [his] lap": Earth's song. A song from her perspective, her voice. A lamentation and a plea.

The chorus came to him first -- a wordless cry. He grabbed his tape player and pressed record. Aaaaaaaaah Oooooooooh.

The chords were simple, but powerful: A-flat minor to C-sharp triad; A-flat minor seventh to C-sharp triad; then modulating up, B-flat minor to E-flat triad. That's it! Jackson thought. He then worked out the introduction and some of the verses. He imagined its scope in his head. This, he determined, would be the greatest song he'd ever composed..."